The Sin City saints who tried to clean up Las Vegas

Driving from Utah to Las Vegas is a singular experience. The dusty scrubland gives way to a gaudy metropolis — a cityscape of misdeeds rising from a desert wasteland.

But it’s here on I-15 that I get the first glimpse of Sin City’s most clean-cut performer. Reflected in my glasses is a single proper noun: “DONNY.”

After ending a resoundingly successful 11-year residency with his sister, Marie, Monsieur Osmond is back in Vegas, reinventing himself once again to keep the crowds coming. This time he’s alone, and the venue has moved up the strip from the Flamingo to Harrah’s, but what hasn’t changed is the boyish performer’s uncanny ability to make us swoon.

After wading through two casino floors, I find my seat at a booth in a cozy theater. I’m almost certainly the youngest member of the audience.

Like clockwork, Donny struts onto the stage to the tune of his ’80s comeback hit, “Soldier of Love.” At age 64, he looks 45. Another two songs in, he’s crooning his trademark number, “Puppy Love,” first performed in 1972. But the show doesn’t dwell in the 50-year past; he hits highlights from his entire career spanning 61 albums, a few Broadway musicals and dozens of TV gigs.

He captures the whole chronology in an eight-minute rap that’s as entertaining as it is self-admiring. Donny also performs a couple of tracks from his latest album that was released last year.

At first blush Donny’s affection for a city that overflows with skin, liquor, gambling and provocation seem paradoxical. Donny’s rap, after all, includes lyrics like “what the hey.” He makes it clear during the show that he’s from Utah and is a devout member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a faith that eschews about nine out of the 10 reasons people vacation here.

But in truth, Donny’s residency is part of a much broader and storied history of many other “Donnys” in Vegas. From missionaries settling on a lonely creek in 1855 to a quiet band of Latter-day Saints that sought to kick out the mob in the ’70s, the little-known Latter-day Saint heritage of America’s most ungodly city has forced more than a few wholesome concessions that have helped shaped Vegas.

If you step out of Harrah’s onto Las Vegas Boulevard, you’ll confront a dizzying jumble of faux-Roman architecture at Caesar’s Palace. To the right is the Polynesian-themed Mirage with its 3,000 rooms. Continue north along the boulevard past several more garish resorts and within a few miles you’ll come to a rudimentary brick wall surrounding a small, dusty plot of land.

It’s the remnants of the Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort, and, as its name suggestions, it’s among the oldest remaining structures in the valley, marking the first permanent, nonnative settlement in the region.

In 1855, less than a decade after Latter-day Saint pioneers first entered the Mountain West, Brigham Young directed a group of 30 men to what the Spanish called Las Vegas — the meadows. Unlike the artificial paradise of the modern-day city, the old Vegas was a true oasis — a fertile valley fed by a natural spring creek. The Paiute Tribe inhabited the region, and the spring served as an outpost for traders and travelers along the Old Spanish Trail.

Young saw the area as helpful to the expansion of Latter-day Saint territory as the meadows began to play a critical role in funneling supplies from California to the Salt Lake Valley.

The 30 missionaries arrived in June and, with the help of Paiute natives, broke ground for an adobe brick fort. After its completion, it stood 150 feet square and provided security from the elements and lawless looters. The settlement also diverted water from the creek to irrigate farmland on which the newcomers attempted to grow crops.

But after two years of poor yields, as well as disagreements among the band of missionaries, the venture fell apart and the Latter-day Saints returned to the Utah Territory.

They left behind both a fort and an open door to growth. That door swung slow at first, but with the turn of the century came the railroad, and rail tycoons soon bought up the land and auctioned off parcels that would eventually become the center of the city.

The new infrastructure led to a population boom, and by 1911 Latter-day Saints had returned to comprise 10% of the population. A century later, more than 2 million people live in the greater metro area, and Latter-day Saints make up about 6% of the population, three times the proportion of their national presence.

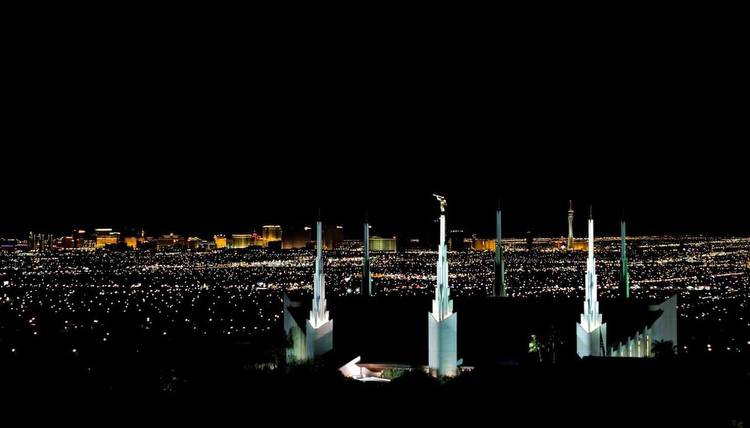

In 1989, a Latter-day Saint temple was built on the east bench of Las Vegas. Members of the faith have held a number of political offices, most notably the late Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, who lived his final years in Henderson, just a 20-minute drive to the southeast. But they’ve also served as state assembly members, state senators, lieutenant governors and district judges.

As longtime journalist John L. Smith remarked, “I don’t think there’s an area of Las Vegas life that has not been touched by the LDS faith.”

Before Reid rose to national political prominence he chaired Nevada’s Gaming Commission, a role that meant confronting Vegas’ seedy side directly.

With in the late 1970s, Reid was offered a $12,000 bribe to give his approval for a casino gaming device and gave a heads up to the FBI. He acted like he would go through with the bribe, so agents could detain the culprit.

When the arrest finally took place, Reid jumped on the man, screaming: “You tried to bribe me!”

“I don’t think there’s an area of Las Vegas life that has not been touched by the LDS faith.”

A particularly Latter-day Saint-Las-Vegas moment came earlier this year during Reid’s memorial service when fellow church member and Nevada-native Brandon Flowers of The Killers performed his song “Be Still” with a postlude that incorporated the Latter-day Saint favorite hymn “God Be with You Till We Meet Again.”

Reid’s son Lief said during the service, “We were shuffling through his songs asking what he wanted to hear. Bob Dylan? No response. Bruce? Nothing. Then we said Brandon — do you want to hear The Killers? And he smiled and gave us a huge thumbs up. So I want everyone know that was the last musical request he ever made.”

Around 4 a.m. on the Sunday after Thanksgiving in 1966, a train slipped into the station at North Las Vegas. A man and his cadre stepped off and were whisked away by a waiting car.

By the shadow of night, Howard Hughes had arrived in Las Vegas.

The country’s most famous billionaire, aviator and Hollywood director — once a celebrity and public icon — had grown increasingly unwell in his later years. He shrank into isolation and conducted business by way of his inner circle. Nobody ever saw him except for a few trusted aides.

Almost all of them were Latter-day Saints.

Years before, at the height of his career, Hughes stationed his operations a stone’s throw from the heart of Hollywood. His office there acted as a sort of headquarters for the businessman’s ventures, from overseeing the Hughes Tool Co. in Houston, Texas, to running an airline, manufacturing military equipment and making movies.

To manage it all, Hughes hired Frank William Gay, a young Latter-day Saint and UCLA student born in Utah. As his work expanded, Gay hired more employees — almost all Latter-day Saints — to dictate letters, record phone calls and otherwise maintain all communications for Hughes, who had started to recede into solitude.

Purportedly, Hughes liked the Latter-day Saints for their diligence, honesty and abstinence from vices. In fact, when a job on Hughes’ team became available, the description was often posted in church meetinghouses around the city.

But Hughes’ life in California began to sour. In the mid-1960s, he found himself at the end of a long and terrible business transaction, which wrecked his mental well-being (no doubt accelerated by lifelong drug use). He left California, and Gay, behind for a new place to call home.

His destination was a city in Nevada with a poor reputation and a thriving mafia operation.

After arriving in Las Vegas in total secrecy, Hughes and his aides, still mostly Latter-day Saints, made their way to the Desert Inn hotel and casino where Hughes had arranged for his company to occupy the top two floors.

The initial agreement between Hughes and the hotel owner was that they would stay for a month. But Christmas came and went, and by the new year, the hotel owner was irritated that Hughes was still occupying rooms that could be reserved for gambling guests. Hughes himself, a troubled, idiosyncratic recluse, had not so much as left his 250-square-foot room since he arrived.

The casino owner threatened to evict Hughes. So Hughes bought the hotel.

The transaction seemed to revitalize an entrepreneurial spirit within the industrialist, and he turned his attention toward the rest of the Las Vegas Strip. He wanted more.

To facilitate the purchases of more hotels and casinos, Hughes found a friend in E. Parry Thomas, a banker who was born in Utah and raised as a Latter-day Saint.

Up to then, no one wanted to do business with casino operators; gambling had ties to organized crime, and it was largely mobsters who benefited from casinos.

Thomas saw the situation differently. Gambling was legal in the state, he reasoned, and as a banker, he had an obligation to do business with any legal entity, sinful or otherwise. He became the first person to lend to the casino operators, which had the effect of quickly expanding the size and number of casinos in town, which also dispersed power away from the city’s worst actors.

Thus he was a natural fit as the man to make acquisitions on behalf of the eccentric tycoon. And because Hughes was worried he would get gouged on the price if his name was listed on the transactions, he had Thomas pose as the buyer.

“Hughes was an American hero to many, and his presence seemed like a signal that the city was turning a corner.”

One by one, the arrangements for each purchase passed back and forth through the hands of Hughes’ Latter-day Saint aides and grew Thomas’ banking portfolio. None of the sellers saw Hughes. The governor gave him an exemption when he refused to show up in person to acquire a gaming license. It was only a quiet group of mostly Latter-day Saints that saw or spoke directly to the ailing man.

The group of confidantes garnered the nickname the “Mormon Mafia.” In a town like Vegas, it fit.

Hughes may have been buying hotels for no other reason than to satisfy his ardor for business and renown, but the purchases made waves. Nevada politicians flaunted the fact that Hughes was in Vegas and was driving out mobsters. Although the truth wasn’t as glowing as they made it out to be (no one in Hughes’ entourage knew how to run a casino and so left many of the syndicate middle management in place), the public’s perception of Las Vegas started to change.

Hughes was an American hero to many, and his presence seemed like a signal that the city was turning a corner.

A more tangible and true improvement came through Thomas’ savvy, however. By law, casinos had to be owned by one individual, a law created in the hopes that the structure would promote transparency and expose organized crime. It had the opposite effect. The mob would often just employ clean frontmen to run the public-facing casino operations while the criminals did their work in the shadows.

Thomas lobbied for a change of law that would permit corporations to own and operate casinos. This change would not only mean good business for Thomas, but also it would subject operations to the scrutiny of the Securities and Exchange Commission and squeeze out the mafia.

It ushered in a new era for Vegas. “Everything I built — the Golden Nugget, Mirage, Treasure Island, Wynn-Encore, were because of (Thomas),” casino magnate Steve Wynn once remarked.

“You cannot say that Las Vegas would be anywhere near what it is today without that tremendous influence of some very dedicated people who happen to be Mormon in faith and practice,” Nevada journalist John L. Smith once wrote. From a desert oasis to a bona fide tourist destination, Las Vegas has Latter-day Saint fingerprints all over it, though they can be hard to spot in a city known for its sins.

Back in Harrah’s, Donny is wrapping up an evening of entertainment suitable for any age. I exit the theater, passing a glass case of his mementos — Joseph’s technicolored coat, the peacock costume from Fox’s “Masked Singer” and a vintage “teenage TV celebrity” Donny Osmond doll made by Mattel.

“Wholesome” is maybe an understatement.

Downstairs, reality hits like an inbox after vacation. Back through the chiming of slot machines and the stench of booze. Out onto the boulevard where the nighttime has brought out droves of tourists. I pass a handful of people hawking smut. A mobile billboard truck creeps along the street advertising “escorts.”

It’s hard to reconcile the dueling paradigms, but longtime Latter-day Saint locals shrug it off. “Las Vegas doesn’t have any monopoly on evil,” a local church leader once said to reporters. “We have no sins here that don’t exist in any other community in the world. It’s just that sins here wear finer clothing, use larger buildings and have larger budgets.”

God-fearing residents in these parts mostly stick to their suburban communities and try to enjoy a normal life in an abnormal town. But even from a distance, their social and political influence stretches the length of the valley.

As I leave for home, I remember a time I asked a Latter-day Saint relative in the north area of Las Vegas how often he and his family venture down to the Strip.

“Never,” he said, “unless we’re going to see Donny and Marie.”