UAW represents thousands of casino workers on the Las Vegas Strip

Las Vegas workers have long called their home a union town, but there’s one seemingly unlikely presence on the Strip: United Auto Workers.

The 89-year-old union known for representing labor behind the American auto industry has been in Las Vegas for more than a decade, but organizing drives in more recent years have brought the membership up from about 400 to 3,000, Local 3555 leadership said.

As other UAW gaming locals step into a national spotlight in big lawsuits and long strikes, the Las Vegas chapter hopes to grow its local presence.

History of local

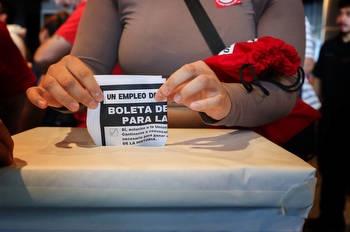

Table games dealers, slot attendants, cage cashiers and count-room employees make up Local 3555. Union leaders say the group grew dramatically through organizing drives at some of the most well-known Strip casinos.

Before then, its membership was in the hundreds, representing dealers and slot attendants at several Caesars properties mid-Strip. Paula Larson-Schusster, a table games dealer at the Flamingo and local president, said the union took over from the Transport Workers Union at her workplace in 2013 and 2014. The next five years saw a big organizing push that culminated in the organizing of table games dealers at Caesars Palace, Harrah’s, Horseshoe (then called Bally’s), Paris and Wynn in 2019.

Ricky Towers, a retired table games dealer at Caesars Palace and member of the local, said workers welcomed the UAW because they knew it had experience with organizing in other markets like Detroit. The union worked toward expanding the contract and adding more units in a way that the previous union hadn’t, he said.

“I think it’s all about the strength of the union, the benefits of the union, how it’s able to navigate to get a labor agreement, and then after the labor agreement, how strong it is to represent,” Towers said. “UAW is the perfect example. They’re probably one of the largest unions in the world, so if somebody comes to say, ‘Hey, we’re the UAW and we’d like to organize,’ you’re going to say yes.”

UAW elsewhere

Other UAW gaming locals have been in the news in recent months, bringing their muscle to contract negotiations and attempted policy changes. In Atlantic City, union members are trying to close the loophole in the state’s Smoke-Free Air Act in a lawsuit filed on April 5.

“UAW and C.E.A.S.E. (Casino Employees Against Smoking’s Effects) members have fought tirelessly to get lawmakers to do the right thing, but politicians have chosen to protect corporate profits over workers’ health,” UAW President Shawn Fain said when the lawsuit was filed. “Today, we put an end to that and ask the court to respect the right of workers to breathe clean air on the job.”

Meanwhile closer to home, Culinary Local 226 — arguably the most powerful union in the state with about 60,000 hospitality members — has ratcheted its labor activity while negotiating a new citywide contract. It threatened to strike at various Strip and downtown resorts before the inaugural Formula One Grand Prix in November and Super Bowl 58 in February. Hundreds walked off the job at Virgin Hotels on May 10 for a two-day strike at the last remaining employer to not reach a deal with Culinary.

Like Las Vegas, the UAW casino workers in Detroit pressured employers to agree to better wages and benefits during a 47-day strike that ended in November.

Growth goals

Local 3555 is following a similar advocacy path to its peers. Like the national union, it elevated its advocacy in favor of smoke-free casino laws by joining forces on a poll gauging Nevadans’ support on the issue.

Leaders say they see the union’s growth and advocacy as hand-in-hand. Towers, who retired in December, said he wants to help the union develop a retiree program and other subject-based committees to develop a central stance on an issue. That way, he said, the union can make stronger cases in negotiations and public policy development.

Others involved in the union say growth hinges not only on adding units, but keeping members involved. Virginia Nunez, the recording secretary and a table games dealer at the Flamingo, said it can be challenging to encourage new workers to join or stop some from dropping who don’t want to pay the roughly $40 monthly dues.

“If people drop out, we don’t have strength in numbers and our ability to negotiate with the company really limits our ability to do that for them,” Nunez said.

Larson-Schusster said she’s focused on the organization’s mission of helping protect workers’ health and safety on the job. When workers inquire about organizing, she said they most often bring up topics of scheduling, seniority, preferential treatment, wages and tip-pooling policies and benefits.

“A long time ago when I first started, we were told to wear push-up bras and short skirts and high heels because that was the only way a woman was gonna get hired,” she said. “It’s not anymore. The companies have come a long ways, but the reason that companies have come a long ways is because the unions have stood up.”

McKenna Ross is a corps member with Report for America, a national service program that places journalists into local newsrooms. Contact her at mross@reviewjournal.com.@mckenna_ross_ on X.