Chicago casino will mean more gambling addiction, experts say

It’s usually a 50-minute drive from Darren G.’s condo in the South Loop to Rivers Casino in Des Plaines. Getting to the Horseshoe Casino in Hammond, Indiana, would take about half an hour.

Darren hasn’t made a trip either way in almost six years, but every now and then he’ll pull up the routes on his phone, taking comfort in the inconvenience of getting to the slots and roulette tables where he estimates he lost more than $94,000 during the depths of his gambling addiction.

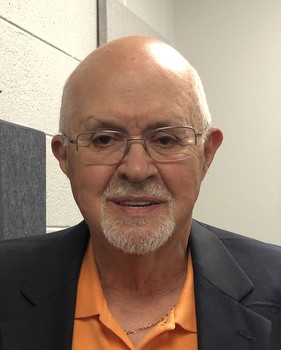

“Any distance or obstacle you can put between yourself and the casino is a good thing,” said the marketing executive in his 50s, who asked not to use his full name.

The distance shrank last month for Darren and the estimated thousands of other Chicagoans dealing with gambling disorder, who face a new temptation with the opening of the city’s first casino in the heart of River North.

With the aid of a sponsor and support group, Darren says he’s confident he won’t make the 10-minute trip up Wabash Avenue to Bally’s temporary casino at the historic Medinah Temple.

But he knows it’s already an easier trip for some problem gamblers — and he thinks it’ll create more.

“A lot of people are about to find out they have a problem,” he said.

Chicago-area addiction treatment experts who spoke with the Sun-Times said that while there hasn’t been an influx of people seeking help for gambling disorder since Bally’s opened downtown, they’re bracing for a steady increase in clients — just like they’ve seen after other gaming expansions in Illinois.

“As new venues come in, people develop new problems,” said Anita Pindiur, executive director of Way Back Inn, a Maywood treatment center that runs recovery programs for people struggling with alcohol and substance abuse as well as gambling disorder.

“The vast majority of people who go to the new casino will spend a little money, have a nice time and then move on. But statistically, we know there is going to be some number of people who are going to need help,” Pindiur said.

It took about six months for Way Back Inn to see an uptick in clients after Rivers Casino opened in 2011. Pindiur said there was a similar lag time the following year, when the state launched a network of video gaming terminals that now includes more than 46,000 slots at 8,400 bars, restaurants and other establishments.

Over the past few years, Pindiur says more than a quarter of new people seeking help at Way Back Inn have come as a result of sports betting, which was legalized in the same legislation signed by Gov. J.B. Pritzker in 2019 that authorized the Chicago casino and five others statewide.

That law and ensuing state budgets signed by Pritzker have boosted funding for gambling addiction counseling. It’s still not clear how many will need it.

200K+ at risk in Chicago

A 2021 state-commissioned study found that 3.8% of adults in Illinois, or about 383,000 people, have a gambling problem. An additional 7.7% — about 761,000 people — were considered at risk for developing a problem.

Those rates suggest there could be more than 80,000 Chicagoans who are addicted to gambling, and 163,000 more who could fall down a dark path.

“That’s Soldier Field, both baseball stadiums and a few other venues filled a few times over,” said Jeremy Klemanski, president of the nonprofit Gateway Foundation, which has a network of 15 treatment centers across the state. “Factor in the families of people struggling with this, and we’re talking about a massive problem.”

Klemanski said while the Chicago casino likely won’t trigger a major spike, he expects Gateway centers to welcome a noticeable increase in problem gamblers within a year.

“When something is more readily available, it’s harder to avoid,” he said. “If you work in downtown Chicago and you have an issue, the commute of driving all the way out to the casino in Joliet might hinder that. That’s gone now for city residents. It’s going to be a lot easier.”

Creating awareness

Klemanski and Pindiur said their facilities are adding additional gambling counselors and beefing up staff training. Along with the state Department of Human Services, they’re also aiming to increase public awareness of a problem that most of those affected don’t even realize they have.

A few of the warning signs: Spending more on gambling than on other entertainment. Losing interest in other hobbies in favor of betting. Missing work or family events to head to the casino. And, of course, falling into financial problems — and continuing to chase those losses.

Klemanski emphasized there are higher rates of suicide among problem gamblers compared to those with other types of disorders.

“It is truly a life-or-death concern,” he said.