How Britain became addicted to gambling

If Sir Tony Blair is in the mood to review his political achievements as he dons the mantle and bonnet of the Order of the Garter for the first time, there is one undoubted success he can bask in. “It is government-wide policy… that Britain should become a world leader in the field of online gambling,” declared a DCMS briefing in 2006. Mission accomplished: betting on football alone yielded operators a gross profit of £1.1 billion in the 2019-20 tax year.

On the other hand, the policy’s responsible aim – “to provide our citizens with the opportunity to gamble in a safe, well-regulated environment” – has not been quite so comprehensively achieved. The 2005 Gambling Act, the major regulatory legislation of Blair’s government, appears to have been drafted by somebody oblivious of the existence of the internet. Media attention focused on Blair’s bizarre and never-fulfilled scheme to build “supercasinos”.

But, as Rob Davies points out in Jackpot, what should have been ringing alarm bells was the ever-increasing sophistication of smartphones: “The modern punter has a supercasino, even several of them, in their pocket.”

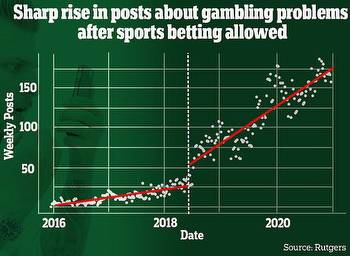

Davies, a Guardian journalist, fears we are on the cusp of an epidemic of problem gambling. This is partly because the industry is working hard to invent new products that “hook our brains into repetitive cycles of play”, from the Fixed Odds Betting Terminals (FOBTs) at the bookies (nicknamed “drains”) to online slot machines; and partly because of the diabolical marketing genius that has seen the industry target and infiltrate football over the past couple of decades.

Not only do we have to endure “the tuberous, disembodied head of Ray Winstone” enjoining us to gamble on commercial television, but even the BBC’s Match of the Day ends up with gambling logos on screen for 70 to 90 per cent of its running time. Such is the industry’s power that many matches now kick off at 8.15pm instead of 8pm, so that the half-time advert break on television starts at 9pm, when the daily embargo on gambling ads is lifted.

Davies chronicles the rather desperate game of whack-a-mole that governments have been playing over the past 15 years as they try to legislate away the industry’s ever more ingenious instances of sharp practice. The problem is that gambling yields the Exchequer huge amounts in tax, so successive governments are too timid to wring more than tiny concessions from the industry, which is cunning enough to get round them anyway. For example, a proposed ban on FOBTs was watered down to a cap on four per betting shop. Bookies simply opened more branches on the same street to meet the demand.

Davies’s eye-opening catalogue of facts and figures is humanised by interviews with gambling addicts and their loved ones (including one addict whose attempt to kill himself in his car was interrupted by doggers), but for an in-depth testimony, turn to Patrick Foster’s new memoir Might Bite, which conveys the grinding misery of living with a compulsive gambling habit.

It is hardly an everyman story – Foster is a public schoolboy who became a professional cricketer – but it does show how anybody can fall prey to gambling addiction. Foster is one of Blair’s children in the sense that in 2006, in his first term at university, a group of friends took him to one of the newly deregulated bookies and he became hooked. His addiction sabotaged his cricket career – “I even batted recklessly so that I… could get back to my bets as quickly as possible” – and he became a teacher at various private schools: clearly a charmer, he managed to con his pupils’ wealthy parents into lending him money, which he gambled away. By the time he sought help after an abortive suicide attempt in 2018, he had borrowed a total of £497,000 from 113 people.

Aficionados of the misery memoir may find it lacking in the spectacular physical degradation that characterises the autobiographies of alcoholics and drug addicts, but what Foster captures so well is the quotidian misery of gambling addiction – not least his reluctance to find a girlfriend because his life is so carefully arranged to provide maximum time for betting – and the petty humiliations, including gambling away money his father has given him to pay off debts, and faking documents that falsely indicate the money has gone to his creditors.

Davies and Foster reach similar conclusions about small steps the gambling industry can take to protect potential addicts: stricter affordability checks, stake limits, curbs on advertising at football grounds. Although some people in the industry – including former MP turned industry consultant Tom Watson – use inflammatory terms such as “prohibitionists” when discussing campaigners for reform, no serious campaigner in Britain is calling for anything anywhere near as draconian as an outright ban.

A government review on regulation, twice postponed, is due this year. But with powerful pro-industry voices in Parliament – notably the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Betting and Gaming, many of whose members have been treated to lavish hospitality by the betting companies – those who know the form book may not be betting on meaningful reform.

Jackpot by Rob Davies is published by Guardian Faber at £14.99. To order your copy for £12.99, call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books. Might Bite by Patrick Foster is published by Bloomsbury at £14.99.