Editor’s Notebook: Off-reservation casino proposals highlight inadequate tribal funding, inequitable federal model

Whether the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians will secure the necessary approval from Gov. Gretchen Whitmer to open a casino in Fruitport Township remains an open question, but the answer will likely emerge within a matter of days.

So far, the tribe has secured approval from the U.S. Department of the Interior to take the land into trust, a necessary step for the tribe’s ability to offer gaming at the location.

However, because the site sits outside of Little River Band’s traditional territory in Manistee and Mason counties, it needs to get approval from Gov. Gretchen Whitmer as part of a “two-part concurrence” process before it can move forward with the off-reservation casino.

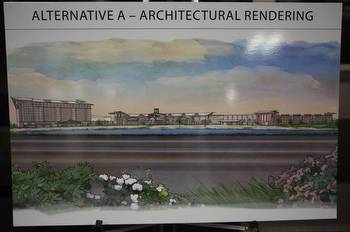

Larry Romanelli, the elected ogema of the Little River Band, remains “quite confident” that the tribe will get the governor’s approval and be able to move forward. Despite opposition from certain Lower Peninsula tribes, Romanelli said he’s heard nothing but support from tribal members and community leaders along the lakeshore for the $180 million to $200 million project.

“They want it so bad,” Romanelli told MiBiz. “We have tremendous support from labor, community groups and businesses because this promotes tourism and economic development and creates several thousand jobs.”

The ball currently rests in Whitmer’s court. Less than a month before the June 16 deadline for her concurrence, Whitmer sent a letter to the Department of the Interior describing what she called a “particularly unworkable” situation involving two tribes.

In the letter, she noted that the deadline to weigh in on the Little River Band’s casino project was June 16, months before the federal government was set to issue a ruling on a petition to recognize the Grand River Bands of Ottawa Indians.

The decision by the DOI’s Office of Federal Acknowledgement ultimately will determine whether the federal government formally recognizes the tribe that historically lived along the Grand River and other waterways in present-day Western Michigan cities including Grand Rapids and Muskegon. OFA set an Oct. 12 deadline for the ruling, but the agency has regularly extended the deadline since July 2017.

“My concurrence with the Little River Band’s two-part determination could frustrate the Grand River Bands, which may wish to open their own gaming facility on tribal lands not far from Fruitport Township,” Whitmer wrote in the letter. “Yet DOI has not provided any information on how likely it is that the Grand River Bands will be acknowledged. DOI is currently scheduled to issue a proposed finding on or before Oct. 12, 2022 — four months too late to enable an informed decision about whether to concur with the Little River Band’s two-part determination.”

If Whitmer were to approve Little River Band’s plan, it would mark only the second time the state has approved an off-reservation tribal casino since the dawn of Indian gaming. The only other occurrence came in 2000, when the Baraga-based Keweenaw Bay Indian Community received state approval to open a second Ojibwa Casino location in Chocolay Township, just east of Marquette.

To date, governors have mostly opposed off-reservation gaming over fears it would set off a cascade of casino projects from tribes jockeying for the most lucrative locations across the state.

Facing opposition

Little River Band’s proposal long faced opposition from three Lower Peninsula tribes: the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi (FireKeepers Casino Hotel near Battle Creek), the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan (Soaring Eagle Casino & Resort in Mount Pleasant) and the Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians (Gun Lake Casino in Bradley).

However, the list grew to include the Grand River Bands, which took a public stance against the casino plans last month when it reacted to Whitmer’s letter.

In a statement, Grand River Bands tribal Chairman Ron Yob said Little River Band was “attempting to pressure the Governor to give away some of our homelands in order to build an off-reservation casino on the treaty lands of our Tribe. This is morally wrong and unjust, and we call on Governor Whitmer to reject this cynical effort.”

Yob acknowledges that the tribe has no formal stance on whether it would eventually pursue gaming, which would be contingent on it receiving federal recognition. Still, he said in an interview that allowing Little River Band to move forward with a project in Grand River Bands’ traditional area was “like shutting the door” on economic opportunities for future generations of his tribe “before they even had a chance to knock on it.”

Romanelli is quick to point out that Little River Band has never opposed another tribe’s casino. He also added that many Grand River Bands members work for his tribe and the two tribes share a “connected bloodline.” With Grand River, he “wishes them the best” in their petition for federal acknowledgement, but sees his tribe’s casino as an unrelated matter.

“It seems like someone’s putting the governor in an awkward situation,” Romanelli said. “The two issues are not related. It’s something two separate tribes are trying to accomplish.”

Tribal squabbles

While the tribal disagreements may titillate outsiders, they’re merely examples of tribes on both sides of the off-reservation casino issue acting in the best economic interests of their members.

Outside of gaming and, more recently, economic development investments, tribes get the bulk of their funding from the federal government. The passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988 was in part an acknowledgment that the federal government would never be able to fully meet tribes’ needs for funding and a move to help them gain economic independence and self-sufficiency through additional gaming revenues.

In the years since, casinos became the economic engines that sovereign tribal governments used to provide services to their members, including housing, health care, education, law enforcement and cultural preservation.

That’s why it’s only common sense that Gun Lake, Nottawaseppi Huron Band and the Saginaw Chippewa would want to preserve their market positions and their ability to serve their people. Likewise, it’s entirely understandable that tribes like the Little River Band would want to find ways to generate more revenue and provide better services to their citizens.

As well, there’s no faulting Grand River Bands from wanting to ensure it has the same economic opportunities as other tribes if it ultimately is successful in securing federal recognition after what’s been a 27-year-long process.

These tribal squabbles are an unfortunate side effect of the politicized system the federal government created for tribes. The disagreements are commonplace in Indian Country nationwide, particularly in states where some tribes have highly successful casinos near densely populated areas, while remote tribes lack the same economic opportunities on their reservations.

Some Indian Country observers note that the system imposed on tribes even incentivizes them to fight with each other, sowing division and discord at a time when tribes should be standing together to fight for more sovereign rights.

Of course, the federal government could always take its trust responsibility for tribes seriously by fully and equitably providing them funding, but that’s not the current system in place — nor is it ever likely to happen.

And so, the cycle of bickering over off-reservation casinos perpetuates every few years.

It also should be noted that, aside from the Little River Band’s plans near Muskegon, most off-reservation casinos have stemmed from tribes in the Upper Peninsula looking to get a foothold in near larger population centers in the Lower Peninsula.

The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians in 2015 pursued off-reservation casinos in Lansing and Romulus, near where the Hannahville Indian Community floated a proposed casino near Detroit Metro Airport a decade prior. The DOI declined the Sault Tribe’s request to take the land into trust.

As well, Bay Mills Indian Community opened a casino south of the Mackinac Bridge on land it owned in Vanderbilt for a few months at the end of 2010 and beginning of 2011. The move tested the tribe’s interpretation of the Michigan Indian Land Claims Settlement Act and resulted in dueling federal lawsuits, which the parties settled in 2020. Under the terms, Bay Mills agreed to wait five years before it attempted to operate a casino on the site.

(Quick historical aside: The Sault Tribe formerly owned a majority stake in Detroit’s Greektown Casino, a commercial gaming venture not governed by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. It later lost the casino to bankruptcy in the Great Recession.)

‘Quite confident’

Despite the 11th hour “misinformation campaign,” Romanelli said the Little River Band remains undaunted in its efforts to push the Fruitport Township casino project over the finish line.

“We’re down to the last few days or a couple of weeks at best. I feel quite confident,” Romanelli said, noting that he was in his 50s when he started working on this project for the tribe and is now in his 70s. “We have it right, we’ve done everything we can. The right thing to do is to approve it.”

The Interior Department gave Whitmer until June 16 to issue a concurrence. In her letter, Whitmer said her situation with the two tribes is “a problem of DOI’s making, and it is a problem that DOI must solve.” She asked DOI to signal by June 1 whether it was likely to rule favorably on Grand River Bands’ petition or else move the deadline for her to concur with Little River Bands’ plans until after the OFA’s Oct. 12 deadline.

Neither have happened as of this writing. A spokesperson for the DOI declined to comment on the “private correspondence.”

If Whitmer does not respond to DOI by the deadline, the agency will consider it as a denial of the tribe’s request for concurrence, Romanelli said.

“In that case, we move on,” he said. “We have services that we have to provide our tribal members.”

He said such a move would be “a big disappointment” for the tribe, its members and the coalition of supporters that the tribe has energized along the lakeshore.

“We’ve invested $30 million-plus. It’s a lot of money for us to pick up and say, ‘we’ll go down the road,’” Romanelli said. “Do we have options? Yes. But they’re not anything comparable to this.”