Connecticut must take on problem gambling

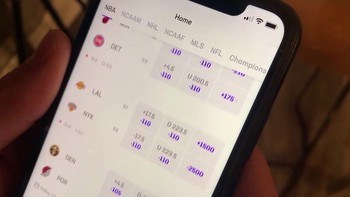

Connecticut has a gambling problem, with online options now making it easier than ever to indulge. Young men appear to be the group most susceptible to addiction, according to a new analysis.

The Connecticut Mirror recently took a deep look at the situation. Increased hotline calls and a lack of resources to help callers were two of the biggest concerns.

“The new thing is people saying, ‘I just lost everything yesterday, because it was football Sunday,’” said Diana Goode, executive director for the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling, which operates the hotline.

The problem-gambling hotline is busiest on Mondays, the day after a day packed with televised NFL football. The broadcasts include lots of ads from DraftKings and FanDuel offering “free play” and “risk-free” bets.

Compared to November 2020, hotline calls were up 87% in November 2021, the first full month after Connecticut legalized online gambling.

Considerable data has been collected on the habits of these new online gamblers that could help shape solutions, but data is only available to casinos and sports books, not the state.

Digital commerce data such as gender, age, hometown, frequency and amounts of betting, and time spent online at the virtual gaming tables is available to DraftKings and FanDuel. Connecticut doesn’t collect that data, which the National Council on Problem Gambling says should be publicly provided in an anonymous form.

In less than three months of online gambling, Connecticut gamblers have wagered $2.6 billion. After paying off the winners, the sports books kept $21.5 million and the online casinos $36.8 million.

The state collected its cut of nearly $10 million. None of it has gone to the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling. While the law is clear regarding the cash flow to the state, it is silent on when the problem-gambling money must be paid and vague as to who is eligible to receive it.

The council’s annual budget is $750,000, primarily funded by voluntary contributions from the two tribal casinos, CT Lottery and the state Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. The council says it can’t afford to add staff or counter the ad blitz under way from FanDuel and DraftKings, the two highest-grossing sports books in the United States.

“Let’s make it a little bit more of a fair fight,” Goode said.

There is much more to learn when it comes to the details of the gambling industry and its impact. But the basic takeaway at this point is as unsurprising as it is disturbing.

Those entities profiting from gambling have free rein. They are waging big advertising campaigns and have access to privileged information about the people who gamble, data that can be used to ensure their consumers stay engaged. Their contributions to efforts that could help stem problem gambling are limited, especially compared to what is spent attracting and keeping players.

The fight should be fair. Data on gambling habits must be shared so good solutions can be put in place, whatever those may be. A fully funded campaign to educate the public on the dangers of gambling, targeting those most susceptible to its addictive qualities, and getting rehab services in place, seem like reasonable approaches.

More must be done if the state is to balance its relationship as a friend of the gambling industry to its need to safeguard those who gamble.

If you need help in Connecticut: Call (888) 789-7777 or Text “CTGAMB” to 53342. New England Gamblers Anonymous Hotline: (888) 830-2217 — Hotline for all New England States.