A Black-owned casino bets on a Black neighborhood in the former capital of the Confederacy

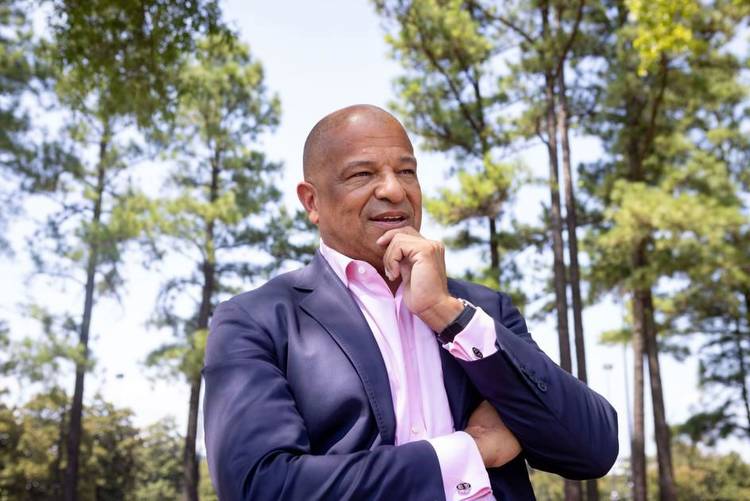

RICHMOND, Va. -Standing in the former capital of the Confederacy on an industrial site he wants to turn into the nation's only Black-owned casino, Alfred Liggins doesn't talk about revenue or market share. He talks about race and equity.

"We always thought we were in the business of serving the African American community," he said. "A big part of lifting up a community . . . is about business opportunities. We viewed gaming for many, many years as one of those opportunities."

Liggins, 56, CEO of media conglomerate Urban One, plans to build One Casino and Resort with a 250-room hotel, a live theater, 1,800 slot machines and 100 table games off Interstate 95 in Richmond's long-neglected, majority-Black Southside. In November, the city will hold a referendum on the project after Urban One beat other contenders to bring gaming to River City.

Gambling and equity make strange bedfellows. Though casinos have proved economic boons to some communities, including Native American tribes, others that embraced gaming look like cautionary tales. With above-average poverty rates, Baltimore, Atlantic City, N.J., and Hammond, Ind., for example, are not known for their robust economies.

Silver Spring, Md.-based Urban One has responded to critics by enumerating the benefits it says it will bring to Richmond: $525 million in new tax revenue, 1,300 jobs paying at least $15 per hour and an influx of 3.7 million tourists annually to a city of just 227,000. Liggins has circulated mailers emblazoned with statistics like these and paid for billboards that read "Richmond Wins, Invest in Southside."

But One Casino must survive a referendum first - one that has divided Richmond in the weeks ahead of November's vote. Even as some community activists and political candidates hailed the casino as the savior of Southside - a gritty strip of trailer parks and weekly-rate motels largely bereft of grocery stores and sit-down restaurants - others denounce the project with yard signs reading: "No Casinos! Keep Richmond Beautiful."

For some, the wounds inflicted on South Richmond by systemic racism can't be healed with roulette.

Quinton Robbins, director of the Virginia liberal activist group Richmond for All, which is campaigning against One Casino, said casino projects offer "the flash of easy revenue" but bring low-quality jobs and gentrification to communities whose current residents are among the city's neediest.

"It's not economic justice to extract wealth from a neighborhood," he said. "This is about the intersection of white supremacy and poverty."

Liggins, remembering a time when it was unlikely that he would become a casino magnate, disagreed with this critique.

"I don't know if this person knows what it's like to be poor," he said.

Liggins's mother - Cathy Hughes, the founder of the company that evolved into Urban One - gave birth to him when she was 17. Even after she founded a business that would become a $300 million behemoth, she was a single mother who, for a time, lived with her son at one of her radio stations on Wisconsin Avenue in Northwest Washington. They couldn't afford a place of their own.

Growing up with less shaped Liggins's thinking about gaming as a business opportunity. He doesn't think casinos prey on poor people. Poor people can't afford to camp out at blackjack tables, he said - and if they spend money on games of chance that statistics guarantee they will lose in the long run, that's their choice.

Gambling is fun, and people have the right to do it, he said, even people who aren't White.

"They're assuming Black and Brown people don't have the sort of intellectual capacity and free will to manage their desires for entertainment, which I kind of find offensive," Liggins said of the project's critics.

Richmond's geography and the inequities it fostered set the stage for this battle.

"Everything's about race in Richmond," said Benjamin Campbell, a retired pastor and the author of the book "Richmond's Unhealed History."

According to Campbell, Richmond's development was concentrated on the north side of the James River as the south side, including 100 acres owned by cigarette giant Philip Morris that Urban One plans to buy for the casino, was left to agriculture and industry.

However, in a bid to keep the city White after desegregation in the early 1970s, Richmond annexed land south of the James. In the wake of subsequent "White flight," Southside became the "most deprived and depleted economic part of Richmond," Campbell said.

This very deprivation made Southside an appealing spot for a casino. After the Virginia state legislature passed legislation last year allowing referendum-approved gaming in Richmond, wealthier neighborhoods on the Northside fought off proposals.

Liggins, who lives near Washington National Cathedral in Northwest D.C., understood their motivation.

"Nobody wants it in their backyard," he said. "I don't want it in my backyard."

But some in Southside want One Casino.

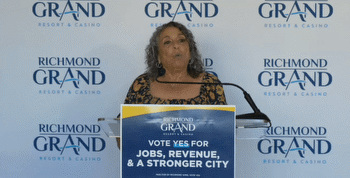

Richmond City Council member Reva Trammell has represented Richmond's 8th District since 1998. Driving through the neighborhood Wednesday in a borrowed tan sedan - her other car's computer was on the fritz - she said that unlike many other White families, hers stayed after annexation.

"When we were annexed into the city, we got nothing," she said. "They abandoned us. I was young. My mom and dad was not going to move. It was called 'White flight.' My mom said, 'I'm staying right here.' "

Touring blocks of single-family homes - many of them listing or in need of paint - abutting the Philip Morris factory, Trammell thrummed with enthusiasm for One Casino. The resort would bring jobs, she said. Tax revenue. Drainage infrastructure for streets that routinely flood during thunderstorms. Live music. Sidewalks.

"Activity, activity, activity," she said.

Trammell flagged down constituents, extracting their opinions. The manager of a Shell station on Jefferson Davis Highway, recently re-christened "Richmond Highway," was for the casino. Turning on to a side street, Trammell abruptly pulled over and leaped out of the car to hug a man mowing his lawn ahead of a thunderstorm.

"He taught me how to play basketball!" she said. The man, who said his son spent a lot of time in traffic commuting to the MGM casino at National Harbor, also favored One Casino.

Leonard Sledge, the director of Richmond's department of economic development, was along for the ride. He offered a less emotional argument for the casino: $170 million in tax revenue in the five years after it opens.

"We just want to make the city better," he said.

Even decades after Native American tribes and cities such as Detroit upended the monopoly on gaming once enjoyed by Atlantic City and Las Vegas, whether casinos make communities better is unclear.

Emilia Simeonova, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Carey School of Business who has studied Native American casinos, said gaming projects have benefited some tribes because revenue is directed to tribe members or because some projects are "in the boonies" without other industries. Casinos may not bring the same benefits to cities.

"Nobody quite knows," she said. "I don't think there is any serious and well-regarded research in economics that shows casinos are good . . . There's no conclusive evidence in either direction."

Sitting in a coffee shop a few miles from One Casino's proposed site, Richard Walker, who runs an outreach program for formerly incarcerated people, said the idea that a casino could benefit Southside was "a lie from the pit of hell."

Walker, a New Jersey native who worked in an Atlantic City casino, said the One project would profit from "low-income community exploitation," increasing traffic and draining customers from other Richmond businesses. As a person who served prison time himself, Walker doubted those with criminal records would have access to casino jobs.

"I'll bet my last dollar on it," he said.

Meanwhile, in Richmond, some are already gaming.

On Wednesday, Patricia Gaines sat with three compatriots in the off-track betting area of Rosie's Gaming Emporium about seven miles from the proposed One site. Here, since 2019, gamblers have been able to place off-track bets and play slot machines as part of legislation designed to support the state's horse-racing industry.

Gaines, who had money on the No. 3 horse in a race simulcast from Saratoga Springs, N.Y., said she moved to Richmond after retiring as a legal secretary 21 years ago. A widow, she lives with two aging pitbulls, Girlie and Rascal, she goes to great lengths to care for. Another dog - Connie, a Yorkie - died at 5 p.m. on April 30 of last year after a battle with kidney failure, she said. The dog, who Gaines had kept in diapers near the end, was 18.

Gaines said she would run about even in her horse-playing career and would vote for One Casino in the coming referendum. She likes gambling. Casino opponents shouldn't keep others from doing what they want.

"They don't have to bet," she said. "They can stay home."